Exiled Austrian and German Musicians in Great Britain

With Hitler’s election on January 30, 1933, most of the political opposition optimistically assumed that things would proceed through established constitutional and democratic processes. An unpopular government would last only until it was voted out again. Checks and balances meant that there was no immediate danger to most Communists, Social Democrats or even Jews, although anyone who had read Hitler’s Mein Kampf suspected that he might be ruthless enough to rid himself of the constitution and rule by decree. Such suspicions were confirmed in less than a month, with the burning of the Reichstag and the beginning of numerous draconian measures. One of these was the dismissal of all Jews from publicly funded bodies.1

As music in Germany was largely financed by federal and state cultural budgets, and as Jews had gravitated towards music in surprising numbers over the decades since the enacting of the Constitution of 1871, thousands of Jewish musicians suddenly found themselves without work. Few thought immediately of emigration, and most had families to support with children attending local schools. The prescient among them may have decided that as long as Hitler was in charge, Germany was closed to all Jewish music teachers and performers, and they may have considered moving to another country in which German was spoken—Austria, for instance, or the German regions of Czechoslovakia and Switzerland. Those who felt confident with French, the most common second language taught in German schools, moved to Paris if they could. Few would have seen England as an obvious first option. Even at that late date, Britain remained cut off from the continent, isolated with and occupied by its slowly diminishing empire. Burma and Singapore seemed closer to the British than Berlin and Munich. Since the end of the war, in 1918, Britain had not only excluded itself to a large extent from artistic developments on the continent: it had also fallen out of love with its own Germanic heritage. England’s ruling Hanoverians had diplomatically changed their name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor, and aspiring British musicians who before the war would have headed towards Leipzig’s Conservatory, founded by Mendelssohn, now looked instead to Paris.

The official reaction to Hitler’s election and subsequent power grab was hardly alarmist in neighboring countries. Many political leaders abroad were no doubt sympathetic to the drastic means that they believed to be necessary in limiting the influence of Jews and Communists, who appeared in both the domestic and foreign media as the natural opposition to Hitler’s “revolution”. It was posited that the opponents were driven by craven self-interest to resist the measures imposed by the Nazis to get Germany back onto its feet. Anti-Semitism was by no means unique to Germany, although in Germany more than any other country, Jews had made great strides within all of the professions, such as medicine, science, the arts and academia. In Britain, the Jewish community was largely made up of refugees, who had arrived following Russian pogroms in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Many had changed their names to sound British; some formed part of London’s East End community, others settled in the working-class districts of Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow. There were, of course, Jewish families that had long been involved in banking and trading, but in general, British Jews had not overwhelmed the arts and liberal professions to the same degree as in Germany. The reasons had to do with the cost of education, the machinations of London’s clubs and a defiantly exclusive class system. An official quota system was therefore not required. The issue of who was acceptable and who was not was entirely self-regulating.

Nevertheless, England still offered one great attraction: access to a safer world beyond Europe. Most German musicians who opted for England from 1933 to 1935 saw it merely as a stepping-stone to the United States, the most desirable destination for anyone aspiring to a new life away from the deep-seated bigotry of the continent. A few who had earlier connections opted for England as a safe place from which to wait out the Hitler years. Most reckoned on a speedy resolution; few believed that a new war would be unleashed. The presumed safety of England, protected by the channel, was not a factor in their thinking, and in the early years of Nazi rule most assumed that they would return to their homes in Germany within a few years.

German and British views of each other

One notion was well-known to German and, later, Austrian musicians who took the plunge to come to England: it was the “country without music”. Most were acquainted with Oscar Schmitz’s Das Land ohne Musik, a polemic published in Munich in 1914 that outlined in some detail how the English lacked a self-produced school of serious music.

If Schmitz overstated his case somewhat in the run-up to the First World War, he was not alone in his opinions. Even Ralph Vaughn Williams was moved to write the following, in 1942:

‘The problem of home grown music has lately become acute owing to the friendly invasion of these shores by an army of distinguished German and Austrian musicians. The Germans and Austrians have a great musical tradition behind them. In some ways they are musically more developed than we, and therein lies the danger. The question is not who has the best music, but what is going to be the best for us. Our visitors, with the great names of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms behind them, are apt to think that all music that counts must come from their countries. And not only the actual music itself, but the whole method and outlook of musical performance and appreciation. We must be careful that, faced with this overwhelming mass of ‘men and material’, we do not all become little Austrians and Germans. In that case either we shall make no music for ourselves at all, or such as we do make, will be just a mechanical imitation of foreign models. In either case, the music which we make will have no vitality of its own’2

It’s equally worth noting that Vaughan Williams does not extend his admiration of German music beyond Brahms, and indeed, following the First World War, Thomas Armstrong, a friend and protégé of Vaughan Williams, stated, in his position as Director of the Royal Academy of Music, that ‘we had to get rid of Brahms!’ He went on to explain that German Romantic influence was stifling English music.3

The Saturday Review of 6 July 1935 described the music of Kurt Weill’s operetta ‘A Kingdom for a Cow’ as ‘a hotchpotch of various styles […] it landed nowhere.’ Frank Howes went even further in his book, A Key to the Art of Music:

‘‘Before [The Seven Deadly Sins] was over I had found my first sympathy with Hitler’s political actions; but I do not in point of fact approve of authoritarian politics, and nothing that happened in the first year of National Socialism encouraged me to have a better opinion of it. Imagine my astonishment, then, when a year later, hearing a very competent diseuse sing three songs by Weill, two from ” The Three-halfpenny Opera,” I once more found myself admitting that Hitler had done well to try and eradicate from German life the kind of mentality reflected in these songs.4

The Musical Times is less shocking in its review of what it calls ‘The Three Farthing Opera’ but writes the following condescending review:

‘Bert Brecht the librettist, and Kurt Weill the composer, have done a queer thing. The one has lifted and altered Gay’s plot, the other has thrown away the well-loved tunes and substituted his own post-war jazzy inanities. It is all very crude and painful. But (to be fair) they know nothing of Gay and [Sir Nigel] Playfair in Germany.’5

It did not bode well for new music coming from Germany and Austria, though there was the occasional bright spot, such as Sir Henry Wood scheduling Ernst Toch’s Second Piano Concerto for a Prom concert on 20 August 1934.

Musical Example 1. Toch piano concerto no. 2 Diane Andersen Philharmonisches Staatsorchester, Halle, Cond. Hans Rotmann (opening only)

As to be expected, the reviews of the work were tepid at best. It was also around this time that Benjamin Britten intended to spend a year in Vienna studying with Alban Berg, only to be dissuaded by parents and teachers eager to protect him from the decadence of Central European influences.

Nevertheless, there were concerted efforts made by the NSDAP (National Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany’ – the official name of the Nazi Party)to promote British music in Germany, though the most that was managed was a concert in relatively provincial Wiesbaden in 1936 of composers such as Bax, Elgar, Holst and a few others, conducted by Carl Schuricht. 1936 would also see the first German tour by a British orchestra since 1912: the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham. Another high-point, in 1938, was Ralph Vaughan Williams’ acceptance of Hamburg’s Shakespeare Medal, an award that was turned down by Neville Chamberlain owing to the appalling treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany. At the same time, Michael Bell, writing for the Observer, would comment on the positive side of musical life in ‘the New Germany’ while mentioning that ‘naturally’ Jews were excluded, as they were not German.6 To a post-Holocaust generation, such confused ambivalence must seem willfully blind at best or murderously bigoted at worst.

Exit UK!

Events would soon overtake questions of where to go. If Austrian Jews working in Germany tended to return to Vienna in 1933, others such as Ernst Toch and Arnold Schoenberg went straight to Paris. To many, it was clear that Germany’s annexation of Austria was inevitable. As early as 1919, the Austrian parliament had passed a measure to be absorbed by its larger neighbor. Its enactment was blocked by the Americans and the French. When an Austrian became German Chancellor in 1933, it must have seemed clear that annexation could only be a question of time. The attempted Nazi coup and the assassination of Austria’s dictator, Dollfuss, in 1934 sent another signal to the politically prescient that it would be wise to leave. When the annexation finally occurred, in March 1938, it was accepted by most of the world as an inevitability that should have been permitted when proposed twenty years previously. The anti-Semitic pogroms that the annexation unleashed, however, astonished Foreign Offices around the world. With the criminalization of the Nazi Party (as well as the criminalization of the Communist Party) by Austria’s right wing dictatorship in 1933, the suppressed rage of a large minority of Austrians exploded.7 The photos of elderly Jews scrubbing sidewalks, along with stories of terrible brutality, galvanized Great Britain into requiring entry visas. In addition, it was made mandatory that they be acquired prior to departure. With even more deadly rampages against the Jewish population in November 1938, it was clear that the world stood on the brink of a major refugee crisis. Worse, most of the refugees were Jewish, and there were already sizeable anti-Semitic contingents in Britain, Canada and the United States.

Quite apart from the political turmoil on the continent, British musicians were not in a position to welcome better-qualified performers. They were aware of the superior training in Germany and Austria, and the financial crisis that had produced a Hitler in Germany had not left Britain immune to economic problems. The advent of sound cinema had closed down countless orchestras and left many musicians on the street.

The BBC and Ministry of Labor issued the expected lip-service promises to the I.S.M. yet went on to intensify their invitations to German musicians after 1933. The Berlin Philharmonic became an established part of the London season until 1938, and the Dresden Opera took up residence at Covent Garden during the summer months of 1936. Though not yet part of Germany, Austria’s many top orchestras and choirs also put in annual appearances. Much to the annoyance of the I.S.M., the public and press welcomed such high standards of technical excellence.

By 1934, the I.S.M. had sharpened its message, and in its house journal, Professor W. Gillies Whittaker made the following astute observation:

The music profession is at the present time faced with a very serious situation on account of political and racial expulsions from Germany. Numbers of refugees are seeking a means of earning a livelihood in Britain. A turn of the wheel in Austria may produce a similar upheaval there, and there will be another invasion of our coasts.

Be it said from the outset that our sympathies are entirely with these unfortunate beings… Our nation has always been in the forefront of helping distressed peoples. But we must face facts. Can we absorb these musicians without dislocating our profession?10

A year later, the I.S.M. could claim success in curtailing the influx of musicians, limiting their opportunities and shortening their ability to remain in Great Britain; the organization openly referred to Jews as predominating amongst recent arrivals and described the ‘enervating influence such foreigners would have exerted upon native musical art.’11With the annexation of Austria, a new push was made against the influx of new arrivals, and it is interesting to see that the Society adopted the editorial position of warning its members not to help individual Austrian musicians without consulting the organization’s executive committee12. The I.S.M. eventually set up a Refugee Musicians’ Aid Committee in an attempt to support musicians who were in transit to other shores; indeed, they saw it as their duty to enable such transit rather than having refugee musicians remain in Britain.

The 1940 policy of internment of all ‘enemy aliens’ relieved the issue temporarily. Most refugee musicians were eventually released – they were considered to be of no danger to the war effort – and the I.S.M. renewed its efforts to curtail their ability to take up employment in any British institution.13 The society accepted, however, the compromise of refugee organizations mounting their own concerts and events. The grievances of the I.S.M. were not without foundation. The fact that refugees were largely Jewish had been downplayed, though not, as shown above, unremarked upon. It gave the distorted impression of a country at war with Germany while taking in Germans who were filling the places of British orchestral players and teachers who had been called up for active service. The Ministry of Labour tried to address these issues. From 1943, the I.S.M. focused its attention on the question of foreign music teachers. There had in fact been disturbing cases of enemy aliens deprived of legal work, offering local children instruction on piano, violin or cello. Some of these cases were followed up with alarming threats of deportation or arrest. Towards the end of the war, the stance had softened somewhat, and with the defeat of Hitler and confirmation of the Nazis’ terrible crimes, the I.S.M. appeared to have accepted the fact that German and Austrian musicians were in Britain to stay.

Music outlets and opportunities in wartime

Although the I.S.M. was defiant in its resistance to foreign musicians encroaching on British terrain, it was only partially successful. The tenor Richard Tauber could not be stopped from performing. Like Pavarotti in more recent times, his popularity extended well beyond opera audiences. The pianist Artur Schnabel, on the other hand, after spending 1933-1939 in Great Britain, while teaching summers in Tremezzo on the Italian/Swiss border, decided that it would be easier to perform in England if he lived somewhere else. In 1939, he and his family immigrated to the United States. But beyond such famous artists as Tauber and Schnabel, a vast assortment of musicians and performers of diverse talents and degrees of status were seeking work. Many were young students, while others were work-a-day voice coaches or orchestrators/arrangers for stage and cinema. There were also approximately seventy composers, of varying levels of prominence, who arrived with the intention of leaving for the United States as soon as possible. Wilhelm Grosz made it to America in time to compose the hit song Along the Santa Fe Trail, which was considered, but not used for the film The Santa Fe Trail, featuring Ronald Reagan, whereas the former Schoenberg pupil Karl Rankl remained stuck in London at the outbreak of war. Paradoxically, Grosz died shortly after arriving in America, whereas Rankl went on to head the re-launched Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, from 1945.

From 1939, the Soviet Union had started to exert its own “soft power,” in the guise of non-political refugee organizations that helped address the daily problems encountered by discombobulated émigrés. They offered language courses, guidance in finding employment, help in tracing relatives and acquiring affidavits and visas. Over time, the organizations branched out to offer a cultural program that included concerts, cabaret, theatre, readings and recitals. With Austrians being considered Germans since 1938, the decision was taken by local Communists, receiving guidance from Moscow, to open up separate Austrian Centers, thus openly refusing to acknowledge the legality of the Nazi ‘Annexation’.

The anti-Nazi propaganda, central to the activities of both the German and Austrian refugee centers, came to an abrupt halt almost as soon as the various organization were founded, with the Hitler-Stalin Pact in 1939. Even British intelligence organizations were wary of overt anti-German campaigns emanating from refugee centers, and recent published research underlines the degree and nature of MI5’s infiltration of refugee organizations.14The outbreak of war would cause further conflicts of interest, as the centers were still not encouraged to agitate against the Third Reich as long as the Hitler-Stalin Pact remained.

Due to the aggressive annexation of Austria on March 11, 1938 and the resulting referendum held under the shadow of terror and manipulated by Nazi cheats; supported by the rights of self-determination as proclaimed by the Atlantic Charter in its guarantee of a new world order; and in respect of the fact that Austrians today remain in bitter conflict with the foreign occupation of Nazi Fascism, the enemy of mankind, freedom, democracy and justice; the Austrians now residing in Great Britain see as their duty to support the freedom fight of the Austrian people and support the victory of Great Britain and the Soviet Union as well as her allies, with all of their available power. For that reason, the undersigned names of individuals and organizations have set upon themselves the following tasks:

1) The retraction of legal recognition by the British government of the violent annexation of Austria

2) The guarantee of right of self-determination for the Austrian people as stated in the Atlantic Charter

3) To mobilize all Austrians living in Great Britain into its own civil defense militia, and to mobilize them in the production of all that is necessary to guarantee the defeat of Nazism by Great Britain and her allies. For this, it is also necessary to remove the status of ‘enemy aliens’ from all Austrians living in Great Britain as well as to strengthen and encourage Austrians still living in their homeland in their own acts of resistance.

The following organizations have signed the petition: The Association of Austrian Social Democrats; The Austrian Centre; Austrian Communists in Great Britain; The Austrian Democratic Union; The Austrian league; The Austrian Office; the Austrian Women’s Voluntary Workers; Austrian Youth Association; Council of Austrians; Kommendes Österreich and Young Austria.

Some background about the Austrian situation is necessary. As early as 1933 and 1934, while Hitler was purging Germany of Socialists and Communists, the right-wing Fatherland’s Front of the dictator Engelbert Dollfuss was doing the same thing in pre-Nazi Austria; most political refugees headed to France. With the fall of France in 1940, they then headed towards Great Britain. This meant that in 1938, when Hitler annexed Austria to the Reich, most of the powerful left-wing political resistance had been neutralized by Dollfuss several years earlier. Indeed, many non-Jewish Austrian Socialists actually believed that the annexation was the “lesser of two evils”: however bad Hitler was, he could not be worse than Dollfuss, or at least so they believed. In addition, they were convinced that Hitler’s policies would ultimately be ineffective and result in his inevitable downfall. This would leave Austria as part of a strengthened, Social Democratic Germany, as had been hoped in 1919, and would save it from the hand-to-mouth existence it had experienced ever since.

The Austrian Centre would play an important role in the specific story of exile for Austrian musicians living in the United Kingdom. Established on March 16, 1939, the Center had an executive committee that consisted of Anna Mahler, Oskar Kokoschka, and Sigmund Freud, who was its honorary president until his death in September of that year. The official opening took place in London’s Paddington district and was attended by Lord Hailley, numerous Austrians and 150 British friends. Patrons were the Lord Bishop of Chichester and parliamentarian Captain V. Cazalet. The Center was housed in a shabby building in Westbourne Terrace; it provided a library with English as well as German books, language classes, a debating club and a weekly newspaper, Der Zeitspiegel. A short time later, it would also become the home of the monthly Austrian newspaper Oesterreichische Nachrichten, with its own publishing company, Free Austria Books, as well as the Free Austria Pen Organization. There was also an employment agency, a lobbying group and an Austrian Self-Help Organization.15The Austrian Centre also included The Circle of Music Lovers; Georg Knepler, who, as a young pianist in Vienna, had accompanied Karl Kraus’s readings of Offenbach, relates the following:

Later, as emigration became a serious issue around 1938, someone founded an Austrian refugee organization where I could work. It was called ”the Austrian Centre,” and during its best years, around 1938 to 1940, it must have had 3,500 members. Most were middle class and non-political people who had to leave because of their Jewish origins.

They were mostly elderly people and politically, assuming that they had a view, it was [fairly evenly] mixed with everything from monarchists to communists. It was founded to make people’s lives easier – I have no idea where they found the money, but there were many people in England who wanted to help. We were able to rent two small houses in London’s Paddington district, where we put a restaurant, a café, a theater and a lecture hall. It wasn’t luxurious, but it was cozy, and people were able to make contact with one another. It made emigration bearable for many. The theater had some excellent actors and the musician wasn’t bad, that was me!16

One of its main propaganda functions, however, was to underline, for the British, the difference between Austrians and Germans. The British government, despite initial disappointment over the Nazi annexation of Austria, ultimately viewed it as legal, and therefore ceased to view Austrians as separate from Germans. The so-called Moscow Declaration of 1943 – the declaration of a separate, independent Austria – did little to alter this perception. Thus, the Austrian Centre’s events were always carefully identified as specifically Austrian, even when they involved nothing more than music, eating, dancing and drinking. The German groups could never allow themselves the luxury of calling themselves “German.” In order to avoid antagonizing their British hosts, they referred to their own events simply as “continental.”17

Competition between the two cultural organizations was evident in their musical activities as on other occasions. Demographic factors, as implied in Knepler’s statement (above), were also significant. In the aftermath of the horrific pogroms unleashed against Jews following the Austrian annexation, Great Britain and other countries barricaded themselves against waves of Jewish refugees by insisting that all would-be émigrés obtain entry visas prior to their departure. Those without foreign sponsorship or bank accounts, or a ticket to another destination, were simply denied entry. The result was that an older, wealthier and more professional class of people arrived from Austria than had been the case when refugees had begun arriving from Nazi Germany five years earlier. “Sponsorship”, always gratefully accepted, resulted in former doctors, lawyers, accountants, musicians, actors, journalists, and their wives and husbands, working as domestics. An entry visa to take a promised job as gardener, nanny or house cleaner would save the lives of many thousands of Austrian professionals and their families. Lord Plymouth, undersecretary for the Foreign Office informed the House of Lords on December 14, 1938, that Great Britain had to date taken in 11,000 refugees. With the annexation of Austria and the fall of Czechoslovakia, the number rose in the following months to over 70,000.18

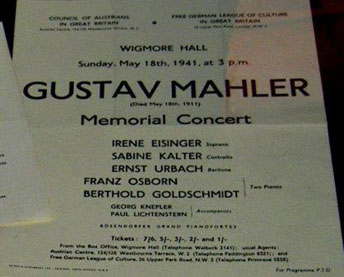

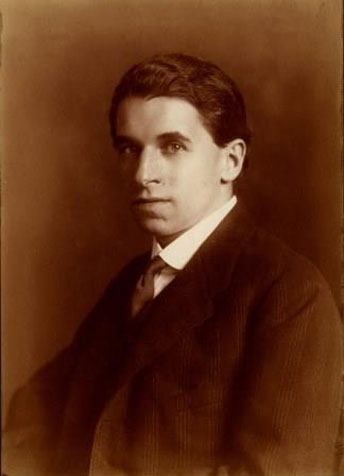

Another demographic difference existed between Austrian and German Jews themselves. Austrian Jews had seen music as a legitimate career option that would provide security and acceptance. This was because Vienna, historically, had placed music far higher than other cultural disciplines. Although few of them came to the UK, prominent Austrian composers of opera and other serious music included Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Zemlinsky, Franz Schreker, Erich Korngold, Egon Wellesz, Hans Gál, Ernst Toch and Hanns Eisler, whereas Germany’s most prominent banned composers of serious music were Kurt Weill and the half-Jewish but Catholic-born and -raised Walter Braunfels. (It should be mentioned, however, that many of the just-named Austrian-born musicians were working in Germany until Hitler’s appointment as Reich’s Chancellor.) The prominence of Austrian Jewish performers revealed a similar discrepancy. All of this meant that in British public awareness, the Austrian Centre could lead where the German Cultural League could only follow. Indeed, both Peter Stadlen and Georg Knepler, in separate interviews, mentioned that Mahler enthusiasm in post-war London was a result of Hans Gál’s four-hand arrangements of the symphonies, performed by the German pianists Franz Osborn and Berthold Goldschmidt at Austrian Centre concerts. Austrian dominance in musical matters played well to British audiences, which continued to accept Austrian composers while banning their German counterparts. In reality, the competition was friendly, and Germans, Poles, Czechs and other Central European refugees performed at Austrian concerts, just as Austrians and the same assortment of refugees from other countries performed for the German Cultural League.

Within the various Austrian organizations, distinctive music groups began to form. One of them, in 1939, was the “Musicians’ Group of the Austrian Circle,” which put on performances by Arnold and Alma Rosé (this was presumably one of Alma’s last public performances before she fell into the hands of the Nazis in Holland). More significant was the “Refugee Musicians Committee,” later called the “Austrian Music Group,” which enjoyed the patronage of Myra Hess, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Adrian Boult and would form the basis for today’s Anglo-Austrian Music Society. The organization was founded by the Austrian pianist Ferdinand Rauter and a number of other musicians, including Hans Gál and Egon Wellesz.

In Rauter’s later explanation, he stressed that politics soured relations between the Austrian Musicians Group and the Free Austrian Movement. At some point, it became clear that a distancing of politics, especially from Soviet influence, was necessary to secure the long-term help that Austrian musicians needed from their British hosts. New contacts were established to secure finances outside the Free Austrian Movement. Social evenings were created, and in time, enough support was found to enable the Austrian Musician Group to be re-named the Anglo-Austrian Music Society (AAMS). Instrumental was the help of Sir John Forsdyke, director of the British Museum, who was married to Dea Gombrich, wife of the Austrian art historian Ernst Gombrich. Rauter’s arguments that political distance was necessary from Soviet influence are weakened, however, by the active participation in the founding of the AAMS by such well-known Communists as Georg Knepler and Hermann Ullrich.20 Another platform for refugee performers was Dame Myra Hess’s series of National Gallery Concerts. Both she and John Christie continued to engage Austrian and German musicians in the teeth of strong opposition and lobbying from the I.S.M. Indeed, the efforts of Christie and Hess overlapped as Glyndebourne, which had started as a vanity project for Christie’s wife, became a net into which the entire musical team of Berlin’s Charlottenburg Opera had fallen: conductor Fritz Busch, administrator Rudolf Bing and director Carl Ebert, along with a host of singers and coaches. What had started as a summer diversion, so that his wife could sing Mozart operas in a converted barn, turned into a major musical event that soon became a high point in the London season.

Performances ceased with the start of the war, which was precisely the point at which Myra Hess began her series of lunchtime concerts in the cavernous, emptied halls of London’s National Gallery; its priceless art collection been moved to safety. The Gallery’s director, Kenneth Clark, referred to a ‘cultural blackout’ with the declaration of war. Myra Hess approached Clark with the view that cultural events provided the ‘spiritual nourishment’ necessary for a country at war. With this in mind, she proposed using the National Gallery for lunchtime concerts in order not to violate the blackout regulations that had closed London’s theaters, cinemas, opera houses and concert halls. Performers who could not work elsewhere managed to perform occasionally under Hess’s auspices. Howard Ferguson was largely responsible for planning; inevitably, the material that best suited the venue was chamber music or works for chamber orchestra. Mainstream classics were central to planning, and Hess herself performed Beethoven, Mozart and Bach.

The BBC also started to provide work opportunities for refugees, although much German music was replaced with music from France and Russia, in addition to British works. But refugees such as Berthold Goldschmidt were able to work for the BBC’s propaganda broadcasts beamed towards Nazi Europe; his programs included works by Mendelssohn and Mahler along with any number of other banned, more contemporary composers. From 1943, the BBC, following the Moscow declaration, opened a special Austrian division that broadcast directly to Austria and underlined its independence from Greater Germany. The BBC also seemed to avoid implementing the otherwise corporation-wide ban on Austro-German musicians by having them perform for their foreign language services. In some rare cases, such as that of Louis Kentner, they were taken up by the entire service. Indeed, Kentner managed to elude the ban on Austrian and German musicians by virtue of his Hungarian citizenship, although he was born in Silesia, which at the time (1905) was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Indeed, Austrian birth before the break-up of the Habsburg monarchy would not inhibit those who had later taken Czech, Polish or Hungarian citizenship. German was still spoken widely in all of these countries and many who may have come across as totally Austro-German managed to evade proscriptive I.S.M. measures by virtue of a Czech or Hungarian passport.

The BBC would also rescue the occasional musicologist, such as Karl Geiringer. In 1935, three years before Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Geiringer had written to the BBC from Vienna and had persuaded the company to perform two Scarlatti cantatas that he had discovered. When forced out of Austria in 1938, he was able to use his BBC contacts to facilitate his emigration, although he was unable to procure steady employment. Ernst Hermann Meyer, who would later become the head of East Germany’s Composers’ Union, was also a valued musicologist who, in contrast to Geiringer, managed to find work at the BBC in a series of Home Service broadcasts on the history of Chamber Music.21

Musical Example 2. ‘They’ from Rankl’s song cycle ‘War’ – Karl Rankl They from the song-cycle ‘War’ sung by baritone Christian Immler with Erik Levi on piano

Opportunities in Peace-time

Suspicion of Austro-German musicians did not abate with the end of the war. In 1945, countless émigrés who had obtained British citizenship were unable to gain visas to return to their former homelands, now under occupation and divided into French, British, Soviet and American sectors. The countries were destroyed, there was little infrastructure left, and the horrors of the attempted genocide against the Jews was such that they were hardly even mentioned. To have died in a concentration camp was almost a mercy compared with the means by which others had survived. It was not something to talk about, and, understandably, Austrians and Germans living in Great Britain showed little appetite for returning. The rebuilding process meant that former Nazis or passionate Nazi sympathizers had remained in their positions unless they had been personally responsible for criminal acts. Even when they were clearly implicated, as in the case of Prof. Erich Schenk, they often had sufficient connections to be let off. Schenk even went on to become Chancellor of Vienna’s University, yet he was accused of having acquired the valuable library of musicologist Guido Adler during the Nazi years by having Adler’s daughter murdered at the Maly Trostinets extermination camp. In spite of this, he was later honored for “having saved the valuable collection for the fatherland”.23Such sobering realities made a return difficult for most former refugees to consider. In letters to Hans Gál from Alfred Einstein and Georg Szell, the anger against the ease with which Nazi colleagues reentered professional life was palpable: “How could I shake hands with a former colleague who goes on to tell me that ‘now that it’s all over, I can say that I never really believed any of that nonsense?’” Einstein asks Gál, in explaining why he refused to return to Salzburg to accept the Mozart Medal. 24

Musical Example 3. Gál cello concerto op. 67, 1944: cello: Antonio Meneses; Northern Sinfonia, Cond. Claudio Cruz (opening of concerto only)

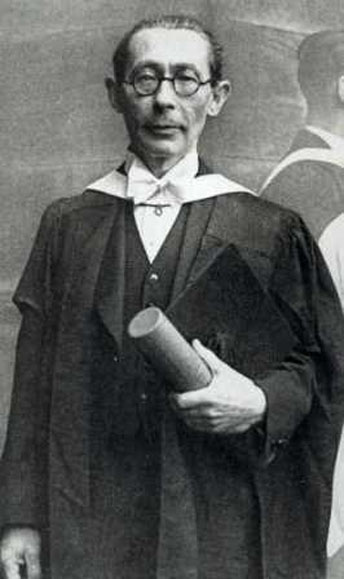

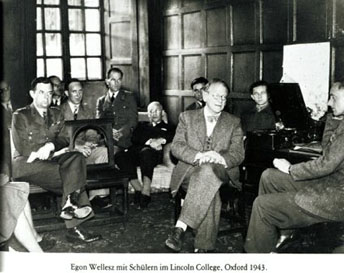

Yet establishing a new British identity, especially as a composer with an established career prior to the Nazi dictatorship, was equally difficult. Youngsters such as Franz Reinzenstein, Joseph Horovitz and Alexander Goehr had an easier time than colleagues who, in some cases, were only a few years older. Composers Hans Gál and Egon Wellesz, for instance, had procured teaching positions at prestigious universities, but neither was engaged to instruct composition and both remained lecturers without ever achieving their previous status as full professors. Gál, for instance, had been Chancellor of Mainz’s famous Music Academy, on the recommendation of Wilhelm Furtwängler and Richard Strauss; Wellesz had been a professor at the University of Vienna and was an established musicologist as well as composer. His international reputation barely registered in Oxford, where being a lecturer in music history and musicology counted for little. Oxford University’s primary musical goal was to train organists for Britain’s Anglican cathedrals.

Musical Example 4. Egon Wellesz: excerpt from Scherzo of III Symphony: Gottfried Rabl and the Austrian Radio Orchestra

Immediately after the war, Wellesz, in common with many other displaced Austrian and German composers, felt compelled to compose symphonies, as if returning to this classical Central European musical form would re-establish earlier cultural identities. Wellesz’s First Symphony was premiered by Sergiu Celibidache and the Berlin Philharmonic; his Second by Karl Rankl and the Vienna Symphony. Adrian Boult commissioned the Third Symphony for the BBC, but it was rejected by an internal panel of nameless controllers. In a letter to his daughter, Wellesz later complained that the people in charge of new music at the BBC were only interested in French music.25 Although the symphony must be counted among his strongest works, it was not heard until decades after his death.

Another opportunity seized upon by émigré composers was a competition put forward by the Arts Council of Britain for a new opera in English. The understanding, and overt suggestion, was that the winning operas would be performed at the upcoming Festival of Britain. Given the fact that such established British composers as Lennox Berkeley, Malcolm Arnold, Albert Coates and Cyril Scott also submitted entries, it comes as a surprise that operas by Karl Rankl and Berthold Goldschmidt were winning choices of the Jury. The submissions were anonymous, thus no one suspected that former enemy aliens would even compete, let along come out on top. Egon Wellesz also submitted an opera based on a William Congreve novel, Incognita. It does not appear to have got very far, though it did enjoy a performance in 1951 by the Oxford University Opera Club. The winning works, on the other hand, were quietly shelved following a flurry of embarrassed correspondence between Arts Council officials and the BBC. Indeed, all of the established émigré composers who remained in the UK gave up composing during various periods. During the war, there were obviously other priorities, but afterwards it was depressing to see how little acceptance was available. Rankl, who had been entrusted with building up the Royal Opera at Covent Garden following its closure during the war-years, was particularly annoyed and imposed a ban on performances of his own works in Great Britain; Berthold Goldschmidt simply gave up composing for the next twenty-four years. 26

Musical Example 5. Old Ships from Berthold Goldschmidt’s ‘Mediterranean Songs’ one of the last works before his 25 year break from composing

The final Balance

Were Austrian and German musicians able to make any impact on musical life in Great Britain? The question is not simple, as their contributions were often vicarious and institutional. There would have been no Glyndebourne or Edinburgh Festival without the contribution of fleeing Germans and Austrians – for instance, Hans Gál in Edinburgh and Rudolf Bing at both. The largest international artists’ agency today, Askonas-Holt Ltd., was partially founded by the Viennese refugee Lies Askonas. Music publishing was nearly overwhelmed by ousted Germans and Austrians. Mahler’s first publisher, the Weinberger company, moved to London, where it became the successful publisher of countless West End and Broadway hits. Although Benjamin Britten was prevented from studying with Alban Berg before the war, his musical mid-wife and closest confidant would be the former Schoenberg pupil Erwin Stein, Britten’s editor at Boosey & Hawkes.

The pianist Paul Hamburger would become the coach of Dame Janet Baker and countless other recitalists, and musicology, which had previously been dismissed as superfluous to university music departments, established itself as a central discipline at Oxford, Cambridge, York, Manchester and Edinburgh. Egon Wellesz’s own specialty was Baroque opera and original performance practices, and most of Britain’s subsequent generations of early music scholars could trace their academic lineage back to former teachers who attended Wellesz’s Lincoln College lectures.

The fact that refugee musicians appear to have made a more direct contribution to musical life in the United States probably has to do with the reluctance of Americans to fret about national identity being swamped by foreign influence. As American culture resulted from various waves of immigration, there was less sense of cultural chauvinism in America than in Great Britain or France. On another level, Ralph Vaughan Williams was not entirely off base when he wrote to Ferdinand Rauter about Germans and Austrians ”trampling the tender flower of British music”.27Britain did not have as strong an international musical reputation as other European nations, and as far as the Germans, Italians or Austrians were concerned, the country was irredeemably unmusical. Vaughan Williams was aware of Germany’s influence on English composers during the latter half of the nineteenth century. It was much later, after studying in France, when he started to develop a nationalistic trend of a sort already long established in Eastern Europe. As far as more soberly grounded Central Europeans were concerned, the “distinctive” British voice that was emerging was modal, impressionistic, conventional and rather shallow. Bartók’s incorporation of ethnic Hungarian music was more adventurous than the Celtic Pastoralism of British nationalist composers, whose works were dismissed by cynics as “cow-pat music.”

The ultimate truth, however, is that Britain did not and could not respond to its musical refugees in any meaningfully different way than other countries of refuge were able to do. No amount of assimilation within new homelands could impose a new cultural identity upon Austrian and German composers. The undeniable success that Kurt Weill found on Broadway was mitigated by the stress that caused his early death at the age of only 50. It could be argued that Joseph Kosma came to represent the quintessence of post-war French chanson with his Jacques Prévert collaborations, but he, like the younger generation of composers who arrived in the UK and America, had yet to establish himself as a composer prior to his departure from Berlin in 1933. If Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky are still considered Russian despite years in America, then what chance would Ernst Toch or Kurt Weill stand? This discrepancy was even more the case with composers who came to England and did not have the advantage of former colleagues, such as Klemperer, Steinberg, Szell and others who controlled the planning of some of America’s leading orchestras. With the exception of Karl Rankl, who rebuilt London’s Royal Opera at Covent Garden, and of a four-year stint (beginning in 1954) in Liverpool by Polish born Paul Kletzki, British musical bodies remained stubbornly in the hands of native British conductors. Berthold Goldschmidt, who perhaps more than others changed his natural musical language in order to fit in, was nearly destroyed when his new homeland deemed him a failure merely for being German. Yet it was never suggested that his actual music was not sufficiently “British;” he had, after all, composed one of the Arts Council’s winning English opera entries. More destructive was the chauvinism that dismissed his work merely because he was not British by birth. Indeed, the reasoning was as racist in nature as the persecution he had undergone as a Jew in his native Germany. With the better part of a century separating us from the defeat of Nazism, it should now be possible to see Germany’s widely dispersed musical exiles as Hitler’s ultimate cultural export. Nevertheless, their chapter in history is precisely that of export rather than import, and for this reason they remain firmly positioned within the story of Austro-German music in the twentieth century. To think of them otherwise is futile.

Posted October 26, 2014

—-

- 1 The burning of the Reichstag on 27/28 Feb. 1933 was followed by ‘The Re-Establishment of a Professional Civil Service’, passed on April 7, 1933. It forbade the employment of Jews in any publicly funded body unless they had served on the Front between 1914-1918. ↑

- 2 Erik Levi quoting RVW 1987, p. 156 in ‘Hans Gál und Egon Wellesz, Continental Britons’ Vienna, Mandelbaum 2004, p.71↑

- 3 Snowman, Daniel: The Hitler Emigrés‘ Chatto and Windus 2002, p. 56↑

- 4 The Musical Times, Review of Howe’s book: September 1935 p. 795↑

- 5 The Musical Time, March 1935 p. 260 Nigel Playfair (1874-1934) was an actor-manager who revived Gay’s Beggar’s Opera in 1920↑

- 6 Raab-Hansen, Jutta: NS-verfolgte Musiker in England, von Bockel Verlag, Hamburg, 1996 p. 76↑

- 7 Though photos show enthusiastic crowds welcoming Hitler, it was assumed that the referendum demanding Austria’s annexation by Germany that Hitler had demanded of the Austria government would not be won. Indeed, the vote went ahead in western Austria where the measure was rejected. ↑

- 8 ‘Music in the Present Crisis’, A Music Journal, The Official Journal of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, November 1931, no page number. ↑

- 9 See Erik Levi in ,Hans Gál and Egon Wellesz Continental Britons‘ Exhibition catalogue, Mandelbaum Verlag Vienna, 2004 p. 74↑

- 10 Ibid, p. 81: as quoted from Professor W. Gillies Whittaker, ‘The Foreign Artist Problem’, A Music Journal, The Official Journal of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, November 1934 , p. 9↑

- 11 Ibid, ‘The Incorporated Society of Musicians. What it has done and is doing for the Music Profession’, A Music Journal, The Official Journal of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, November 1935 , p. 11-12. ↑

- 12 Ibid, Editorial Notes: Austrian Refugees, A Music Journal, The Official Journal of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, May 1938, p. 63. ↑

- 13 The internment of enemy aliens is such a complex and dense subject that I have not covered it in this essay. The best account can be found in the recently published English translation of Hans Gál’s camp memoirs ‘Music behind Barbed Wire’ published by Toccata Press, London 2014↑

- 14 Brinson, Charmian, Dove, Richard: A Matter of Intelligence, Manchester University Press 2014 Chapters: ‘The largest Communist sideshow in London: The Free German league of Culture’; ‘The Austrian Centre’ and ‘The Czech refugee Fund’ pp 115- 157↑

- 15 Pross Eichborn, Steffen: In London treffen wir uns wieder AG Frankfurt am Main, April 2000. p. 167 ↑

- 16 musica reanimata Journal no. 40 Georg Knepler in conversation with the University of Hamburg Exile Music work group on December 3, 1992, Hamburg↑

- 17 Raab Hansen, Jutta: NS-verfolgte Musiker in England, Bockel Verlag 1996 p.308 ↑

- 18 Birgid Leske Exil in der Tchechsolowakei in Großbritannien, Skandinavien und Palästina, Reclam Leipzig 1987↑

- 19 Die Gruendung der Anglo-Austrian Musikgesellschaft Ferdinand Rauter datiert nur als 1976, Archive of the Anglo-Austrian Society↑

- 20 Bearman, Marietta; Charmian Brinson; Dove, Richard: Wien – London, hin und retour Czernin Verlag, Vienna 2004, p. 162↑

- 21 For the above and much of what follows, I am indebted to Jutta Raab Hansen and her invaluable NS-Verfolgte Musk in England, von Bockel Verlag, Hamburg 1996 References to Kentner, Geiringer and Meyer: pp 152-161 ↑

- 22 Ibid, p. 168 quoting a memo from K.A. Wright to Reginald Redman from 28.October 1941: found in the BBC ‘WAR, Karl Rankl, Artists, File 1: 1938-1943, p. 2 ↑

- 23 This extraordinary case is now well documented in the Egon Wellesz Collection at the Austrian National Library, nevertheless, Wikipedia has subsequently posted in German an usually detailed, and accurate account of the case in its entry on Erich Schenk↑

- 24 Letter from Alfred Einstein to Hans Gál 15 February 1947, Bavarian State Library #414↑

- 25 Egon Wellesz to Elisabeth Wellesz-Kessler, 16th November,1952. ÖNB-M, WF 13 ↑

- 26 Lewis Foreman offers an in-depth and somewhat subjective presentation of events concerning the Arts Council competition in his essay for the British Music Society, special number 2004↑

##